Are Space-Based Data Centers in our Future?

AI in Space: Hype, Physics, and the Real Path Forward

Introduction

TL;DR AI computing is about to hit limits on Earth—especially electricity and cooling—so putting AI in space is starting to look less like science fiction and more like an engineering roadmap.

This post is going to address comments that were made in my last Prophecy Roundtable where the team (Pastor John Haller, Britt Gillette, Patrick Wood, and Pete Garcia) began to think through putting AI in space.

Note: I will be on Pete’s REV310 live stream this Wednesday January 7. This is one of the topics on the agenda. Also note that I’m working on a second article entitled “The Death Trap of Total Satellite Coverage” that goes with this discussion. Look for those links soon.

Elon Musk argues that if civilization keeps advancing, “AI in space is inevitable.” He frames it in terms of energy: if humanity wants to reach anything like a Kardashev-scale civilization (one that uses a meaningful fraction of the Sun’s power), Earth is a tiny energy budget. He claims Earth receives only a tiny fraction of the Sun’s energy and suggests space-based solar-powered AI compute could become the lowest-cost option surprisingly soon, perhaps within 4–5 years. He also points out a very practical bottleneck: if you look at modern “AI racks,” a huge portion of their size and mass is taken up by cooling hardware. In space, he argues, cooling becomes “just radiative,” and solar becomes continuous—no night, no batteries, fewer material needs like glass and heavy framing. This is a very compelling roadmap.

Sabine Hossenfelder agrees space has strong energy benefits and avoids land constraints. But it pushes back on the simplistic idea that “space is cold, so cooling is easy.” In a vacuum, you can’t rely on convection airflow, which is the everyday method used on Earth. Heat must be moved through materials to large radiator panels and then emitted as infrared radiation. Both Elon and Sabine state that passive radiators are the best way to cool ultra-hot chipsets from Nvidia and other manufacturers.

There are two other major constraints:

Radiation which can damage chips and cause compute errors, and

Bandwidth space-to-Earth links are far slower than data center networks

Put together, the story becomes clear: AI in space is probably real—but it will arrive in stages, starting with space-native workloads, not “train everything in orbit tomorrow.”

AI is becoming an energy and cooling problem

When most of us think about AI, we think about chatbots, image generators, or robots. But under the hood, AI is basically math at massive scale, and math at massive scale means electricity. Lots of it. And whenever you use electricity to do work, you create heat. Lots of it.

That’s why this topic keeps showing up in boardrooms and on big stages. Sabine sets the tone by talking about “AI factories”—a phrase Jensen Huang (here) uses to describe data centers that generate intelligence the way factories generate products.

Jensen’s point is that older computing was often “retrieval-based” (you stored content and fetched it). Now it’s generative, meaning content gets created on demand, for each person, in real time. If the world is going to run on real-time generation—text, images, software, simulations—then it needs an enormous, always-on computing backbone. That’s where the “factory” metaphor comes from.

Musk then takes that idea and asks: if we’re going to build something like a global network of AI factories, can Earth actually handle the power generation and cooling infrastructure required?

His answer: not at the scale he’s imagining.

Top 5 most interesting points

1) Musk “AI in space is inevitable”

When Musk says “AI in space is inevitable,” it can sound like a headline designed to go viral. But there’s a serious argument underneath it: energy is the ultimate limiter.

He frames it with a Kardashev-style lens: if you want to turn a meaningful slice of solar energy into “useful work,” you don’t do that by staying on a planet that receives only a small fraction of the Sun’s output. He even throws out a striking comparison: Earth receives roughly a “one two-billionth” fraction of the Sun’s energy (his wording). Whether the exact ratio is perfect isn’t the main point—his point is directionally true: space is where the energy is.

Think of it like this: Earth is like trying to run a massive factory on a single extension cord. Space is like stepping outside and plugging directly into the power station—if you can build the equipment to use it.

2) Cooling is the secret villain

Musk argues that a huge fraction of modern AI “rack” mass is cooling. He says something like: if the rack is two tons, almost all of it is cooling hardware. His point is that cooling is not a side issue; it’s the bulk of the physical problem.

On Earth, cooling often works like this:

Hot chip

Air or liquid moves across it

Heat gets carried away by moving fluid (convection)

Heat gets dumped into the environment

In space, there is no air. That means convection doesn’t work in the normal way. So you’re left with:

Conduction: move heat from chip into a plate/pipe

Radiation: dump heat into space by emitting infrared energy from radiator panels

That’s why satellites often have those big panel-like structures—radiators aren’t decoration; they’re heat management.

3) The strongest near-term use case

The single most practical use case is likely: process data that starts in space.

Satellite links have limited bandwidth. The explainer points out a dramatic mismatch:

Data centers can move information around internally at terabit-per-second speeds.

Satellite-to-Earth links are more like gigabit-per-second.

That’s like comparing a firehose to a drinking straw.

So if a satellite collects huge amounts of imagery or sensor data, it can be smarter to do AI processing up there—filter, compress, detect objects, flag anomalies—then send down only the results.

This is where Musk’s vision can still fit, but with a realistic sequence:

Step 1: Put inference (AI “use”) in orbit for satellite data

Step 2: Build clusters for more complex in-orbit workloads

Step 3: Only later, if networking and architecture improve, consider truly large-scale training in orbit

In other words: space AI begins as edge computing—AI near the source of data.

A word about performance from ookla (here):

Although Starlink said its goal is to deliver service with just 20 milliseconds (ms) median latency, the lowest median latency rates recorded by Speedtest users in all or portions of the selected states was 38 ms in the District of Columbia and 39 ms in Arizona, Colorado and New Jersey. Alaska and Hawaii have the highest latency rates of 105 ms and 115 ms respectively. The higher latency rates in these two states is likely due to these two states being more geographically distant from Starlink’s constellation of satellites and not having the same density of satellites as the continental U.S.

4) Radiation is a big deal

A major challenge is cosmic radiation and solar particles. Radiation causes two problems:

Permanent damage over time (electronics degrade)

Transient errors (bit flips) that can corrupt computations

That second one matters a lot for AI. Training and inference rely on massive numbers of calculations. If you get silent math errors, your results can drift in strange ways. That means space compute must be designed like mission-critical systems: error correction, redundancy, shielding, fault tolerance.

One way to mitigate this is to put satellites in lower orbits, because they have less radiation than deeper space. Shielding helps, and so does radiation-hardened chips exist but can be slower.

5) AI factories vs AI satellites

Jensen’s AI factories idea is an Earth-first engineering and infrastructure solution. Huge data centers are generating real-time intelligence for people, companies, and countries. Musk’s AI satellites idea is space-first. It uses solar-powered orbital compute scaling beyond Earth’s grid.

These don’t have to be competing visions. A more realistic future is hybrid:

Earth-based AI factories do most training and most human-facing workloads (at least for a long time)

Space-based compute handles space-native data, strategic workloads, and eventually large-scale compute where energy economics justify it

High-speed interconnects (like the laser link concept mentioned in Source A) act as the “backbone” that makes distributed space compute possible

If you want an analogy: Earth data centers are today’s cities. Space compute could become the highways and offshore ports—specialized infrastructure that changes the economics of trade and movement, but doesn’t replace cities overnight.

Risk / Rewards

What’s the reward if this works?

Energy scale: Space solar can be abundant and, in principle, continuous in the right orbit. Musk argues that at very large compute demands (hundreds of gigawatts to terawatts), Earth’s power plant buildout becomes unrealistic, pushing compute off-planet.

Less land and permitting friction: No land purchases, no local water battles, no zoning fights.

Space-native intelligence: Faster and cheaper processing of satellite imagery, climate monitoring, disaster detection, maritime tracking, secure comms—anything where the data originates in orbit.

Strategic and defense value: Governments may pay for high-reliability orbit compute for secure and resilient systems.

What’s the risk?

Thermal systems are heavy and unforgiving: Radiators and thermal pipes add mass and complexity, and failures are hard to fix.

Radiation resilience isn’t optional: You need shielding, error correction, and redundancy. That can mean slower chips or more hardware.

Bandwidth constraints limit general workloads: Unless networking improves dramatically, sending huge training datasets from Earth to space is inefficient.

Launch + replacement economics: Even if rockets get cheaper, you’re still shipping physical infrastructure into orbit and maintaining it in a harsh environment.

Net: High reward, high complexity, likely to succeed first in narrow use-cases before it becomes “the new normal.”

Space AI will be cheaper in 4–5 years?

Here’s the conversational, fair answer: he might be directionally right long-term, but the 4–5 year claim is the risky part.

Why?

Because “cheapest AI compute” depends on all-in cost, not just electricity. And space adds costs that Earth doesn’t:

radiation shielding

thermal hardware sized for radiative cooling

fault tolerance

launch cost

orbit operations

replacement strategy

debris and collision avoidance (not discussed much in your transcripts, but it’s real)

At the same time, Musk’s point about Earth-side constraints is also real:

power grids are strained

permitting is slow

cooling and water use are political issues

AI demand is growing rapidly

So the blended view looks like this:

Space AI becomes compelling quickly for space-native data (because it avoids bandwidth limits by processing in orbit).

Space AI becomes compelling later for massive-scale compute if energy and cooling costs on Earth keep rising and launch costs keep dropping.

In a blog post, a clean way to phrase it is:

The first wave of space AI won’t replace Earth’s data centers. It will complement them—especially for satellite data and high-value workloads. The “train everything in orbit” dream depends on breakthroughs in networking, thermal engineering, and space operations.

Summary

AI in space will happen first not because it’s cool, but because it’s practical—especially when the data is already in space and Earth can’t afford to move it fast enough or power it cheaply enough at scale.

ATTENTION: So, you’ve read this article. Are you seeing something very important? Let’s compare notes.

Musk owns the entire technology stack here. He’s not going to stop driving towards this capability. Think about it, Brothers and Sisters. He owns the space launch platform (SpaceX), he owns the largest AI data center in the world (X-AI), and he has access to unlimited capital.

Second, we already know how to do radiative cooling in space. No brainer.

Third, we already do radiation shielding in space. No innovation required.

There is a red herring about latency. The amount of time it takes to beam information from a satellite to earth is indeed much longer. But my question to you is: did you catch the first use case: process data that is already in space! This is presented like it’s some big problem, but that’s nonsense in my opinion. Processing data is space is what this is all about, actually.

How does the beast system wire up the world? You can’t put enough copper or fiber in the ground…too little too late too expensive. Next week’s post “The Death Trap of Total Satellite Coverage” will explore this more. Here is my hypothesis:

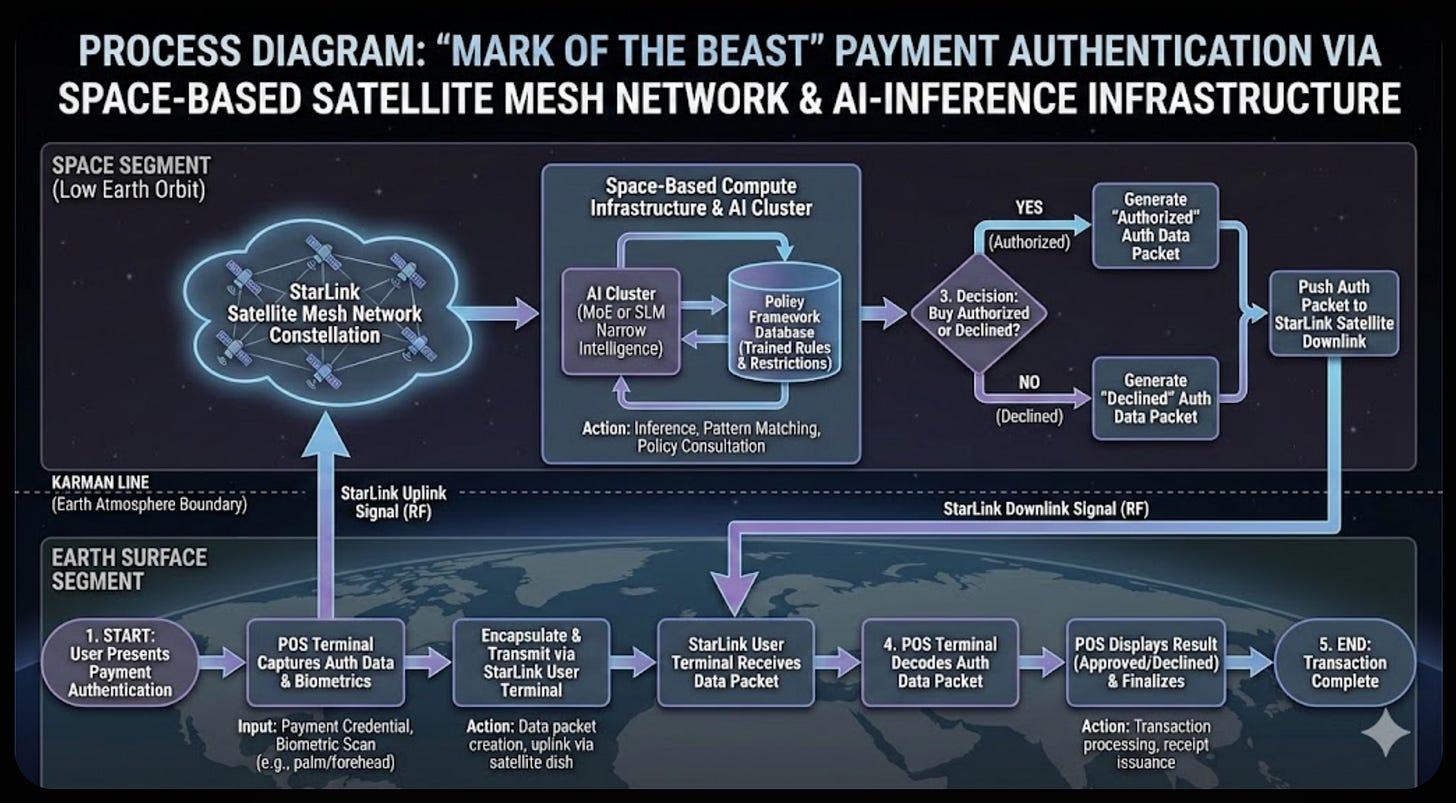

Put AI-based inference in space-based platforms. Look at the hero image on this post for what that could look like. Inference is about getting information FROM an AI, not putting it INTO AI. It’s stupid to train in space. There’s no need to. A LLM model of 30B parameters can run on my MackBook M4 pro and take up only 17.2GB of data! At the kind of speeds they are talking about—which they characterize as slow, it still only take an hour maybe to send the pre-trained Mixture of Expert (MoE) models that are highly tuned up to the AI clusters in space.

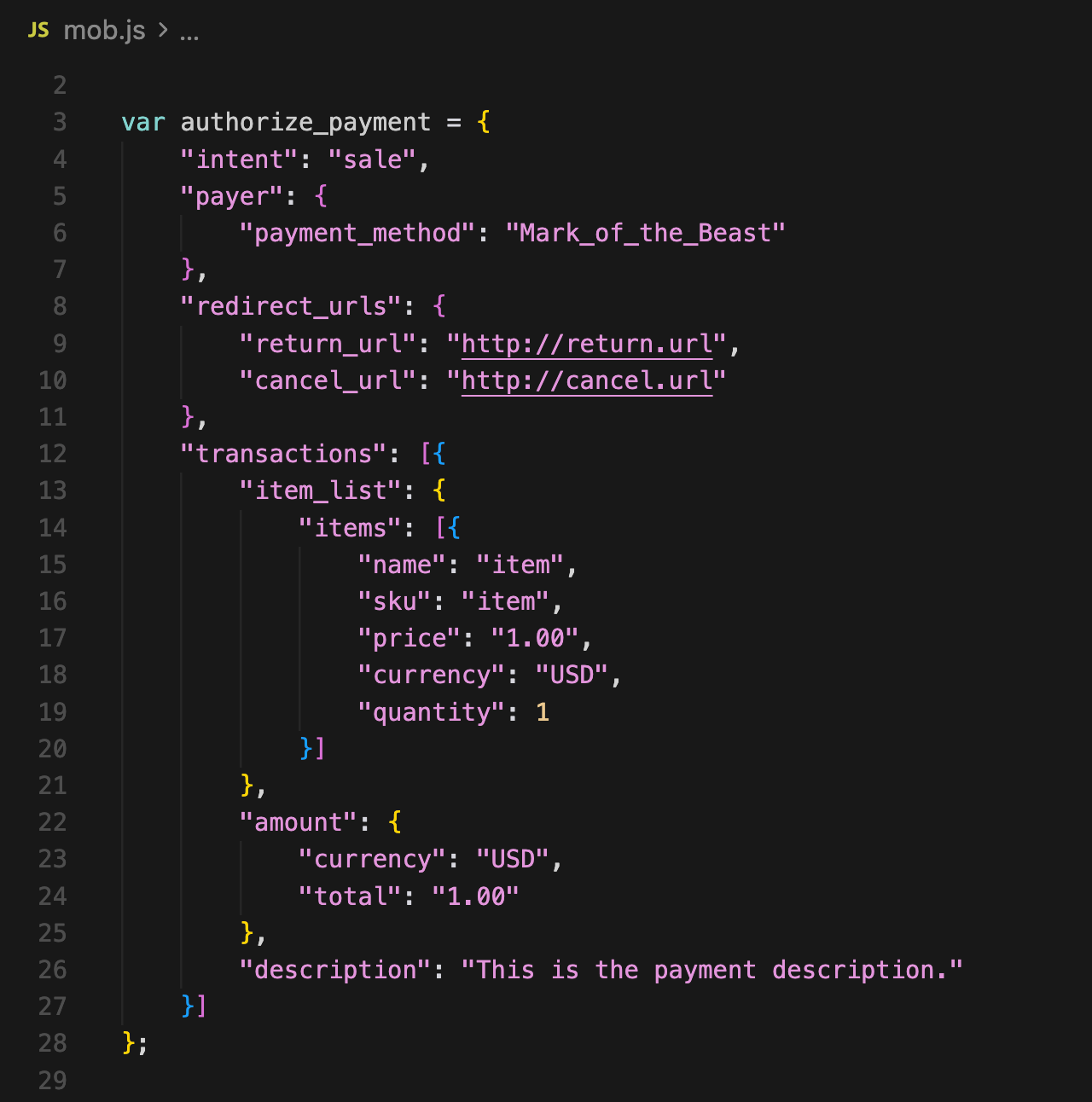

What do we know about the Mark of the Beast? Let’s focus on payment authentication only, for a moment. A person at a store wants to pay for something. At the register, they “present” the Mark, whatever the form factor is. It’s easy to do, just present your right hand or scan the forehead. No big deal, this is already being done today with RFID chips injected under the skin or OCR for QR or barcodes. Here’s something for you to consider. This is all the data such as transaction needs to push:

This transaction only consumes 650 bytes. That’s tiny! Billions of these transactions are flowing around per millisecond.

Continuing to think out loud here. StarLink uses laser pulses to communicate with each other (here). Lasers, hmm, speed of light, right? If those lasers can point to an AI-based cluster orbiting in proximity to any node, I don’t think that’s a long process. It is virtually instantaneous.

What kind of AI LLM is required to run the Beast System in space? Let me clarify. A general purpose LLM design is massive, having over 1T parameters. But they don’t need an LLM. What they need is a SLM (Small Language Model, here). Also known as a MOE (Mixture of Experts), all that I believe is needed is the policy of the Mark enforcement. It’s a decision gate in classic architecture. Here is a process diagram. You can pinch/zoom to see more detail.

The main point I want to make

What makes sense to our team on the Prophecy Roundtable and others I’m sure—and to me—is that Mark of the Beast infrastructure NEEDS to be in space for maximum control! After all, a ground-based data center can be sabotaged. It can also suffer the effects of the series of judgements that Revelation talks about. No earthquakes in space, right? No 100 pound hail either.

Stay tuned for next week’s post on StarLink.

Let me know your thoughts and tune into Pete’s REV310 channel on Wednesday for a more robust discussion on this topic. All the technology needed to do this is here. Nothing news is required.

#Maranatha

YBIC,

Scott

My son's response:

"Well that was a pretty good article, until we got to the "ATTENTION" section, where it goes a bit weird.

Problems:

Musk does not have "unlimited capital" - no one does (other than God!). He's wealthy and influential, but even his enterprises eventually need to turn a profit.

Speaking of profit, OpenAI, one of the largest AI companies, is a long way off profitability. I just heard figures that suggested an annual turnover of something like $11bn, with losses at around $76bn (I forget the exact figures). That's not sustainable.

I think the author is wrong about AI training. From what I hear, it's one of the biggest problems in AI at the moment. Companies are spending billions creating model-training infrastructure, which is considerably more powerful than the author's MacBook Pro.

The "mark of the Beast" clearly has a strong spiritual implication in Revelation, almost regardless of your particular eschatology. A device used as a payment method (like an RFID chip, in your phone, your watch or your wrist) is not a spiritual thing. It's a tool, no more or less evil than a screwdriver.

"Artificial intelligence" isn't intelligent. It doesn't know anything. It's just a sophisticated language generator with a massive dataset. Half the fear of AI comes from misunderstanding its nature.

I'm personally a bit more concerned about the actively hostile intentions of certain atheistic foreign states. But all of these concerns must be subject to the power of Almighty God.

AI factories in space? Puny!"

Should people not use Starlink when no other internet is available? I imagine Starlink users are helping them fine tune their technology